COGNITIVE SEMANTICS: ARGUMENT IS WAR

For the scientist, truth is objective and

absolute. The standard theory of truth is the "Correspondence

Theory": a statement has an objective meaning, specifying the conditions

under which it is true. Truth consists of a direct correspondence between a

statement and some state of affairs in the world.

A theory of truth entails a theory of

Meaning. Linguistics, a social science, seeks to apply the theoretical and

methodological principles used by the natural sciences (with physics as the

model). These also called empirical sciences depend on the formal sciences

(mathematics and logic), which contribute to build the theory of truth already

mentioned.

According to different theories of meaning,

the objective meaning of a sentence is described as the conditions under which

this is true or false. Semantics is the study of how linguistic expressions can

fit the world directly, without the intervention of human understanding.

Meanings are assigned to words without referring to particular contexts of use.

The world is made up of building blocks, i.e., definable objects and clearly

delineated inherent properties and relations.

The problem of meaning is directly related

to the bi-directional influence between subject and object. Konrad Lorenz, the famous naturalist, considers this a crucial matter; he states that in order

to avoid subjective criteria (prejudice and emotions) and to achieve

universally valid judgments and evaluations we need to penetrate into the

cognitive processes of the perceiving subject.

"The process of cognition and the properties

of the object of knowledge will only be able to be investigated when they are

undertaken simultaneously. The object of knowledge and the instrument of

knowledge cannot legitimately be separated, but must be taken together as a

whole".

Terms like 'metaphor' came to traditional grammar from the long-lasting discussion held by Classical Greek scholars on the subject of the origin of the rules which govern language. For some of them, language was a matter of convention, a tacit agreement among members of a community, reinforced through custom and tradition. For others, language has its origins, as Lyons puts it, "in eternal and immutable principles outside man himself," principles which are therefore inviolable. The relevant issue in this discussion is that of the nature of the meaning-form relation of words. For the naturalist school, the relation between a word and its meaning is a 'natural' one, in the sense that a word either resembles its referent (onomatopoeia) or is suggestive or imitative of some qualities or activities of things (sound-symbolism). There are however many more cases of words whose natural meaning is extended through a series of processes such as addition, deletion, substitution, and transposition of sounds, on the one hand, and metaphor, on the other. For the Greeks, metaphor was based on the discernible connection observed between the shape or function of the primary and secondary referents. In this way, naturalists explained "metaphorical extensions" such as the mouth of a river or the leg of a table. These early attempts on a theory of language meaning proved to be very useful for the developments of etymological studies. But, as Palmer remarks,

"It may seem obvious that foot is appropriate to mountains, or eye to needles, but a glance at other

languages shows that it is not. In French the needle does not have an 'eye',

and in many languages (e. g. the Ethiopian languages or some of those of North

America) the mountain does not have a 'foot'. Moreover, in English eye is used with a variety of other

meanings, e. g. the centre of a hurricane or a spring of water, which are not

so obviously related semantically to the organ of sight, yet it is not used for

the centre of a flower or an indentation, though these might seem intuitively

to be reasonable candidates for the extension of the meaning".

Linguistic tradition has recognized, to a

great extent, if not totally, the literary authority over the subject.

Therefore, it is of no surprise that for most linguists the concept of metaphor

differs only slightly from that of the literary tradition. It is generally

described as an exceptional event among the rest of linguistic phenomena, as a

kind of marginal meaning (Bloomfield). The first approach to metaphor linguists seemed to have had was

that it is a case of semantic violation, a deviation from the 'normal', 'logical'

meanings of utterances, what Leech describes as "the process whereby

literal absurdity leads the mind to comprehension on a figurative plane". The distinction made was, in general, between a literal meaning and

a metaphorical one. The metaphorical meaning was achieved through processes of

non-logical meaning production accounted for in terms of ambiguity, paradox,

contradiction, etc. The production and understanding of metaphors in these

terms depend on the creative aspect of language, which differs from Chomsky's

competence in that it refers to voluntary, conscious creativeness, i.e.,

the one required in poetical works. Traditional and structuralist linguistic

trends have, at best, developed a way to make apparent the kind of 'anomaly'

present in metaphors, whatever this anomaly might be.

Other authors consider metaphor a process

more useful for historical linguistics. To illustrate this approach, let us

take Robins' definition of metaphor, who conceives of it as a means whereby

the meaning of a word changes through time.

"A very extensive type of

semantic widening consists in metaphorical uses, wherein on the basis of some

similarity of the meanings a word is used in different sorts of contexts and in

reference to different sorts of features, usually of a more abstract nature,

than once was the case. Metaphorical extension of meaning... is too well known

to require exemplification".

Similar examples of the little attention

paid to metaphor is seen in language comprehensive works, like those of Quirk

et al. and Palmer, who simply relate it to figurative,

non-literal, and transferred meaning. Greimas groups images, symbols,

and metaphorical definitions as 'figures' without a practical function in logical

language, and therefore only interesting to literary studies. Figurative

meanings replace literal meanings as 'bricolage' only to serve to 'something

else', which is the poetic communication itself.

An early understanding of metaphor as a

crucial aspect of language function and thought can be found in Ogden and

Richards' Symbolism, i.e., the study of the influence of language upon thought.

They state that language meaning operates within a universe of discourse,

"a collection of occasions on which we communicate by means of

symbols."

"When we say... "The sun

is trying to come out," or "The mountain rises," we may clearly

be making no different references than if we were to give a scientific

description of the situation, but we may

mean these assertions to be taken 'literally'... interpreting our symbols... as

names used with a reference fixed by a given universe of discourse".

When we do not have a symbol at hand we can choose one

whose referent is analogous to our referent and transfer this symbol. Then if

the speaker fails to see that such symbol is metaphorical, i.e., if he takes it

literally, "falsity arises, namely the correct symbolization of a false

reference by which the interpreter could be misled".

Furthermore, whenever a term is taken outside the universe of discourse for

which it has been defined, it "becomes a metaphor, and may be in need of

fresh definition".

"...reference... cannot be

formed simply and directly by one grouping of experience, but it is the result

of varied groupings of experiences whose very difference enables their common

elements to survive in isolation. This process of selection and elimination is

always at work in the acquisition of a vocabulary and the development of

thought. It is rare for words to be formed into contexts with non-symbolic

experience directly, for as a rule they are learnt only through other words. We

early begin to use language in order to learn language, but since it is no mere

matter of the acquisition of synonyms or alternative locutions, the same

stressing of similarities between references and elimination of their

differences through conflict is required. By these means we develop references

of greater and greater abstractness, and metaphor, the primitive symbolization

of abstraction, becomes possible. Metaphor, in the most general sense, is the

use of one reference to a group of things between which a given relation holds,

for the purpose of facilitating the discrimination of an analogous relation in

another group".

The use of metaphor, according to these authors,

involves the same kind of contexts as abstract thought; the important point is

that the members of "a group of things" will only possess the

relevant feature in common, and that irrelevant or accidental features will

cancel one another.

"The metaphorical aspects of

the greater part of language, and the ease with which any word may be used

metaphorically, further indicate the degree to which... words have gained

contexts through other words".

Here what matters is the reference process

itself and its discursive purpose; the structure is irrelevant. As can be seen,

as far back as 1923, Ogden and Richards stressed the basic relationship among

thought, language, and metaphor; an approach that has only recently been taken

into account.

Within generative semantics, there is a

large amount of different approaches to metaphor in relation to a

semantically-based linguistic analysis of anomalous sentences and their

contribution to the elucidation of semantic selectional features (Galmiche). An extreme example of this wide range of conceptions is that of

Thorne: he tries to explain the existence of 'ungrammatical', 'deviant'

sentences in poetry by postulating the poet's creation of "a new language

(or dialect)" in which the semantic selectional restrictions are different

from those in the normal language. However, he never takes the concept of

metaphor, nor even that of connotative meaning, into account.

Lakoff proposes a theory which

analyses sentences in terms of their logical structure, surface structure, context, and conveyed meanings. According to

this author, the "literal meaning" of a sentence is a function of its

logical structure and its derivation into surface structure. The conveyed

meaning of a sentence is explained in terms of the relevant aspects of context.

Consequently, two different lines of investigation can be adopted in semantics, one dealing with language

structure and the other, with language use, that is, with Pragmatics.

Nevertheless,

"Most grammars have been

concerned exclusively with literal meaning, and this kind of analysis is

necessary before a meaningful study of pragmatics can begin. ... in comparing a

system like generative semantics to that of case grammar, it is the analysis of

literal meanings that must be compared, not the conveyed meanings...pragmatics

left aside". (Cook)

A sociolinguist approach to metaphor is

that of Grice, who suggests a general CO-OPERATIVE PRINCIPLE

between speaker and hearer, including the 'maxim' of quality: "Try to make your contribution one that is

true." Grice points out that this maxim "...is flouted by irony and

metaphor (You're the cream in my coffee)

-and the hearer has to work out what it is that the speaker is trying to

convey."

A pragmatic approach to metaphor is that of

Searle, who postulates that the phenomenon of

metaphor is related to the difference between sentence/ utterance meaning and speaker's meaning. In a

metaphorical expression, both the literal (sentence) and the metaphorical

(speaker's) meanings are present, the former being the explicit message and the

latter what the hearer must comprehend through searching something the speaker

utters that is not expressed when the sentence is interpreted literally. What

is uttered is an attribution of some features of the second term to the first

one, and both components of metaphors are related so that both must be taken

into account if utterance meaning is to be determined. 'X' restricts the range

of meaning that can be recognized in the metaphorical sentence and in the

speaker's utterance. The hearer or reader understands the metaphor's utterance

meaning (which makes sense of the original sentence, or the metaphor) attending

to these restrictions. In Searle's own terms, "the combination of S and P

(subject terms and predicate terms of a metaphorical sentence) creates new R's

(the predicate of the utterance meaning). We have a specific set of associations with the 'P'

terms, but different 'S' terms restrict the values of R differently". To illustrate this, he uses two metaphors:

Kant's second argument for the trascendental deduction

is so much mud/gravel/sand paper.

Sam's voice is gravel.

Both metaphorical meanings are different

because of the difference between Kant's

argument and Sam's voice. The

predicate gravel has different

meanings in each sentence. We subscribe Searle's conception in the following

respect: there is a selection of some features from all the possible features

lying in the connotative depth. But the idea that the selection is based on the

type of subject that fills X position seems to be rather structural. The

meaning to be conveyed by the speaker depends on what the speaker himself wants

to convey, together with the context in which the metaphorical utterance is

performed. The hearer must therefore make use of a complex set of clues to

decode the underlying meaning, including the specification of the subject

defined (X), knowledge of the world shared by both participants, the personal

information the hearer has about the speaker, the immediate context of situation, seriousness on the

part of the speaker (who may be being ironical, e.g., saying Lucy is an angel when both participants

know that she is not good or compassionate at all; in this sense, seriousness

can be included in the shared knowledge or even in the immediate context, so

that there seems to be considerable overlapping), and many others. Searle says

that in cases like Sally is a block of

ice we just perceive a connection which is the basis of the interpretation;

these connections, according to Lakoff, coincide with the system of

Conceptual Metaphors, a central part of synchronic linguistics. Nevertheless,

in his account for literal meaning, Searle subscribes "the usual false

assumptions that accompany that term." Everyday, conventional

language is literal and not metaphorical in its nature, therefore metaphor is

in the domain of principles of language use.

"...we can see why most philosophers of

language have the range of views on metaphor that they have: They accept the

traditional literal-figurative distinction. They... say that there is no

metaphorical meaning, and most metaphorical utterances are either trivially

true or trivially false. Or... they will assume that metaphor is in the realm

of pragmatics, that is, that a metaphorical meaning is no more than the literal

meaning of some other sentence which can be arrived at by some pragmatic

principle. This is required, since the only real meaning for them is literal

meaning, and pragmatic principles are those principles that allow one to say

one thing (with a literal meaning) and mean something else (with a different,

but nonetheless literal, meaning)".

The term connotation is crucially important to delimit the approach to

metaphor in semantics. Connotative

content is distinguished from denotative

content (also labelled, dictionary

or central meaning by different

authors), which overlaps with the notion of reference,

a criterion for the correct use of a word provided the properties (semantic

features) which define that word. Connotative meaning is the communicative

value an expression has by virtue of what it refers to, over and above its

purely conceptual content. This is why some authors considers connotation as a

part of pragmatics (Baldinger). There is a multitude of additional

non-criterial properties that we have learned to expect a referent of a word to

possess, beside its 'neutral' denotation. Connotative meaning has been viewed

as more attached to reality itself than to language proper, a peripheral

phenomenon depending on the context of expression and, for that reason, unstable,

depending on the particular cultural and historical period, and on the

experience of an individual speaker. While the denotative, central meaning of

an expression has the form of a finite set of discrete features of meaning,

connotation is open ended, infinite as our knowledge and beliefs about the

universe. An interesting example of this distinction is the one given by Leech when he lists the denotative features related to the word woman:

[+ human]

[- male]

[+

adult]

Leech includes next physical, psychological, social characteristics, "typical

concomitants of womanhood", and putative features:

[+

biped]

[+

having a womb]

[+

gregarious]

[+

subject to maternal instinct]

[+

capable of speech]

[+

experienced in cooking]

[+

skirt or dress-wearing]

[+

prone to tears]

[+

frail]

[+

cowardly]

[+

emotional]

[+

irrational]

[+

inconstant]

[+

gentle]

[+

compassionate]

[+

sensitive]

[+

hard-working]

[-

trouser-wearing]

It is evident that such a list of

constituents may be infinite and that they are highly dependant on cultural

biases, as well as on sex, age, personal opinions, preferences, and so on.

Whenever a sentence or a word is uttered, it maps both a connotative and a

denotative meaning, since every expression of language is uttered by a given

person in a given context. metaphors

are forms of expressing this connotative meaning. The connection between the

terms in a metaphorical relation lies in connotation. The denotative meaning is

left aside while some of the numerous connotative meanings are selected as

underlying semantic features of a

word, e.g., Lucy is an angel. The

denotations already stated for woman

do not fit the ones we can attribute to the notion of angels (this is why

linguists in general treat metaphors as semantic violations). But from all the

connotations of woman only a few are

mapped onto angel, which in turn has

equally numerous connotations of its own. We reckon that woman's selected connotative features such as gentle, compassionate, sensitive, are mapped onto a group of some

connotative features of angel, such as generous,

incapable of evil, suffering, and so on. The use of a metaphorical

expression triggers an automatic, arbitrary, and totally new selection of

underlying connotative meanings, which remain implicit in what we may call the

underlying structure of denotative

meanings, until they are mapped to the surface by a metaphor. Needless to say,

when we utter Lucy is an angel we are

by no means saying that she is not a human being, or that she is a religious

entity, or 'non- specified' in terms of sex and age; what we are in fact

expressing is a kind of 'non-neutral' definition of Lucy. This metaphor is, in fact, part of everyday language (a dead metaphor); it functions as an

'economical' device, one through which we can mean a great deal of information by using only one word. The

indeterminancy of the semantic features the metaphor conflates (Lucy is a very good, generous,

compassionate, and suffering woman, incapable of any evil act) can be

viewed as a sort of implicit contract of meanings between the speaker and

his/her interlocutor(s). The specification of such features is always limited;

the metaphorical expression could be telling us more, or perhaps less, about Lucy than a 'literal' one. This issue

will be dealt with in the next chapter. The amount of information to be

included in a metaphorical expression can only be solved by the speakers of the

language according to the conceptual world they share and the concrete

situation they are in. Furthermore, in many cases the hearer has to decode from

a complex of clues that which corresponds to a specific connotation selected by

the speaker according to what he/she intends to express through a metaphor.

When someone chooses the word angel instead

of saint, he/she has searched for the

most suitable word, in a particular situation, occasion, and time, and has

undertaken this complex task automatically, almost as if he/she were using this

word in its "neutral" meaning. As Widdowson puts it, "the

effect of metaphor depends on avoiding the resolution of ambiguity: the user

keeps two meanings in his mind at the same time." We can argue

that an expression such as Angel is

an available container of three levels of meaning that a speaker can make use

of; according to Harman these levels are: thoughts (denotation/

connotation), communication of thoughts, and speech acts. We consider speech

acts as constituents of the second level since they depend on a speaker's

particular choice or intention, and the third level corresponds to the context

of culture and situation, in

Malinowsky's terms. Suppose speaker A and speaker

B and Lucy are all people living in the United States in 1993 and that they are

acquaintances. Speaker A has a low opinion of Lucy and he says "Lucy is an

angel". The actual meaning of Angel

must be decoded along the following clues:

Obviously, the picture here proposed can be

much further extended, including, at the first level, all the types of

connotative meaning; at the second level, the diversity of speech acts that can

be performed; at third level, nationality, social class, age, etc.

At this point, explicit metaphor comes into

view as not being at all a peripheral phenomenon in language, but instead a

very extended one in terms of use within the linguistic universe. The issue of

conceptual (that is, implicit, not linguistic) metaphorical meaning in everyday

language will be analysed in the next chapter.

Cognitive semantics, as a theoretical paradigm, claims

that lexical concepts must be studied against the background of the human

cognitive capacities at large. In other words, it holds that if language is one

of the fundamental cognitive tools of man, it should not be studied

autonomously, as if it contained a semantic structure that is independent of

the broader cognitive organization of the human mind (which is the basic

structuralist tenet). By contrast, cognitive semantics holds that there is no

specifically linguistic-semantic organization of knowledge, separate from

conceptual memory. Consequently, lexical semantic research should be conducted

in close collaboration with other sciences that study the human mind and its

working principles in order to find out how man comprehends, stores and retains

information, and expresses human experience, be this specific to the individual

or to his culture. This implies, for example, that attention should be paid to

cultural differences in the metaphorical patterning of experience, as do a

number of authors, in an effort to individualize semantic universals operating

as general strategies for coping with part of human experience.

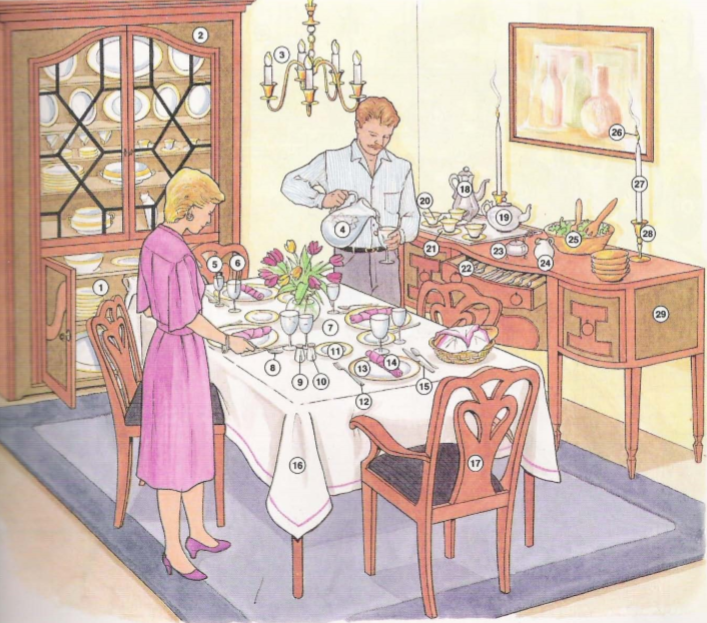

Gallagher, in the context of formal thought

research, emphasizes the importance of the system of correspondences in

Piaget's theory:

"Simple examples of correspondences (or

morphisms in mathematics) are the places set at table for each invited guest or

a test mark for each student. The relationship formed is called a mapping. In the familiar one-to-one

correspondence -that is, isomorphism- each element of the first or original set

has one, and only one, corresponding element from the second or image set".

Analogy and metaphor are, therefore, very important

devices for structuring knowledge; they are also crucial in scientific

reasoning because they provide richness and wider scope to arguments and

descriptions, and supply a powerful and creative framework for scientific

exploration, one that is "not possible with ordinary discourse or with

propositional reasoning." According to Ortony,

"Metaphors are necessary as a communicative

device because they allow the transfer of coherent chunks of characteristics

-perceptual, cognitive, emotional and experiential- from a vehicle which is

known to a topic which is less so. In so doing they circumvent the problem of

specifying one by one each of the often unnameable and innumerable

characteristics; they avoid discretizing the perceived continuity of experience

and are thus closer to experience and consequently more vivid and memorable".

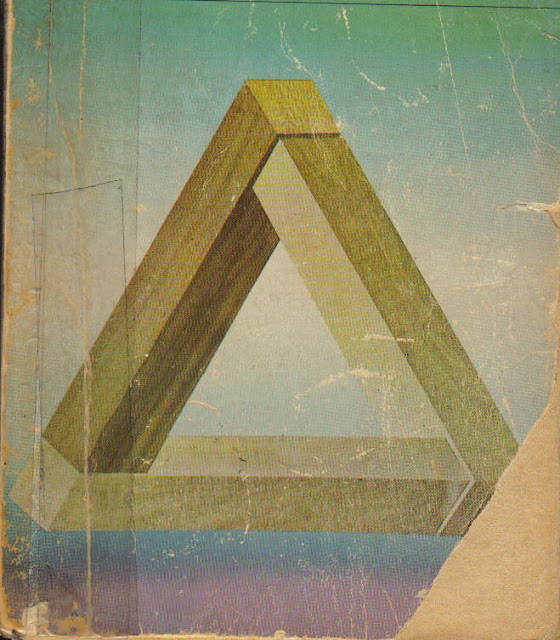

Cohen considers a metaphor as a mapping of the

elements of one set on those of another.

A map is a system, and their elements are in

correspondence with the mapped system;

this correspondence may take a large number of forms: "a map must

be isomorphic with the mapped system with respect to some of its features." Gallagher concludes that metaphors are much more than the

simplistic form A is B, and that they

are complex comparisons, involving tension elimination: a shift from central

meaning to marginal meaning.

THE THEORY OF

CONCEPTUAL METAPHOR

The theory of Conceptual Metaphor, as a cognitive

approach, is basically concerned with understanding. According to Lakoff and

Johnson, the traditional scientific views cannot cope with human

understanding in the long run: it emphasizes the fact that there are real

things, existing independently of us, which constrain both how we interact with

them and how we comprehend them. It focuses on truth and factual knowledge due

to the importance they have for our successful functioning in our physical and

cultural environments. It is well known that the eighteenth-century scientific

world conception is an extension of common sense: reliance on the senses and

empirical proof through technological advances.

According to Lakoff and Johnson, we all think and act

according to what we assume to be true. “Absolute truth" cannot be

achieved. This claim is based on the principle that the acquisition and use of

truth depends on our understanding of the world we live in. Human understanding

can be characterized in terms of categories emerging directly from our

experiences as human beings. This categorization of the world is defined as

follows:

... a natural way of

identifying a "kind" of object or experience by highlighting certain

properties, downplaying others, and hiding still others.

This is the origin of categories such as OBJECT,

SUBSTANCE, orientational categories (IN-OUT, UP-DOWN, etc.) and many others

according to which we define objects and situations. The properties

highlighted, downplayed or hidden in the process of categorization are to be

found within natural dimensions which make up gestalts in terms of which

objects and situations are categorized. These natural dimensions range from

perceptual and functional to purposive and causative ones. Early approaches to

these notions were proposed by Lennenberg and Lorenz when trying

to give an account of the natural and bodily dependence of human behaviour and

understanding.

Categories are built according to a sequence that goes

from CONCRETE to ABSTRACT (NON-CONCRETE), CLOSE to APART, PHYSICAL to

NON-PHYSICAL, DEFINED to NON-DEFINED, etc. In other words, we primarily

comprehend and know the world through

this process, and thus we play "tricks" in conceptualizing whenever a

matter of knowledge is abstract or undefined; we take another concept or object

to concretize, come close, or define the former. Lakoff and Johnson examine the

basic concept of Causation, taking into account the building-block theory, the

Piagetian theory of manipulation, and the theory of prototypes. The concept of

causation is based on the prototype of DIRECT MANIPULATION, which develops

since we are children. The prototypical core of a concept is not

"primitive", i.e., it is not an unanalizable semantic schema, but

rather a group of elements perceived as a unity prior to its components,

namely, a gestalt which consists of properties that naturally occur together in

our daily experience, when we perform direct manipulations.

A good example of the way we categorize is that shown

by a statement like I've invited a sexy

blonde to our party. In this description, attention is focused on

only a few dimensions and properties of the person being referred to, due to

the fact that the purposes for which the expression is required have determined

this focus of attention; had these purposes been different, the properties

highlighted would certainly have been others (for instance,

the colour of her eyes).

Properties are not inherent to objects or situations

but are rather the product of human interaction with the world around, and it

is this interactional nature of properties which constitutes the basis for our

notion of what is true and what is not: something will be true for us if it

"makes sense only relative to human functioning." Thus, a

true statement will involve the choice of categories of description, which in

turn involves both our perceptions and purposes in a given situation; besides,

it will leave out what has been downplayed by the categories used. That is why

statements like I've invited a sexy

blonde to our party and, let us say, I've

invited a Marxist to our party can both be true about the same person

referred to.

All this accounts pretty well for statements easily

correlated with our daily experience, like I

live in Chile, but what about statements which do not so clearly fit our

knowledge of the world, for instance, the

fog is in front of the mountain? The answer involves the concept of

"projection": when our basic categories do not fit our reality, we

project them onto objects and situations, and thus assign orientation to what

does not have it inherently (a mountain) or entity structure to what is not

clearly delineated as an entity (a mountain, the fog), etc. This is how we

manage to understand everything in terms of a number of basic categories of

understanding. This concept of projection is essential to see how we can

understand some things in terms of others, that is, how we conceptualize

metaphorically.

Although proposed by Lakoff and Johnson - respectively, a well known linguist (who has contributed to cognitive

semantics since its earlier developments), and a philosopher of science- the

theory of Conceptual Metaphor can be traced to Michael Reddy's paper

"The Conduit Metaphor", where he analyses the way everyday English

person conceptualizes the concept of communication: his contention is that we

do not literally "get thoughts across" when we talk; rather, this suggests

that communication transfers thought processes somehow bodily. Actually, no one

receives anyone else's thoughts

directly in their minds when they are using language. A speaker's feelings can

be perceived directly only by him/ her; they do not really "come through

to us" when he/she talks. Nor can anyone literally "give you an

idea" -since these are inherently internal processes.

...[some examples] seem to involve the

figurative assertion that language transfers

human thoughts and feelings. ...if language transfers thoughts to others, then

the logical container, or conveyer, for this thought is words, or

word-groupings like phrases, sentences, paragraphs, and so on.

The logic... we are considering... called the conduit metaphor... would now lead us to the bizarre assertion that words have "insides" and "outsides." After all, if thoughts can be inserted, there must be a space "inside" wherein the meaning can reside. ..."content" is a term used almost synonymously with "ideas" and "meaning". ...recollection is quite meaning-full (sic). ...Numerous expressions make it clear that English does view words as containing or failing to contain thoughts...

...of the entire metalingual apparatus of the English language, at least seventy percent is directly, visibly, and graphically based on the conduit metaphor.

Reddy uses this theory and a considerable amount of

data to demonstrate that everyday language is largely metaphorical; that the

locus of metaphor is thought, not language; that metaphor is a major and

indispensable part of our ordinary, conventional way of conceptualizing the

world; and that our everyday behaviour reflects our metaphorical understanding

of experience. In Lakoff's words, Reddy "gave us a tiny glimpse of an

enormous system of conceptual metaphor. Since its appearance, an entire branch

of linguistics and cognitive science has developed to study systems of

metaphorical thought that we use to reason, that we base our actions on, and

that underlie a great deal of the structure of language."

The theory of conceptual metaphor used as theoretical

framework for this study is the one proposed by Lakoff and Johnson in Metaphors

We Live By. In essence, this theory holds that our conceptual

system, and therefore our language, is largely metaphorical in nature. A large

section of their book is devoted to demonstrate what it means for a concept to

be metaphorical and the pervasiness this phenomenon has in language as a whole.

The most important claim we

have made so far is that metaphor is not just a matter of language, that is, of

mere words. We shall argue that, on the contrary, human thought processes are largely metaphorical. This is what we mean

when we say that the human conceptual system is metaphorically structured and

defined. Metaphors as linguistic expressions are possible precisely

because there are metaphors in a

person's conceptual system. Therefore, whenever... we speak of metaphors... it should

be understood that metaphor means metaphorical concept.

A Conceptual Metaphor (CM) is a mental phenomenon, the

inner, unconscious, cognitive conceptualization of a domain of experience: entities in the world, actions, states,

people, living beings, etc., perceived in terms of another domain of experience

of an entirely different type. This conceptualization, applied to almost every domain, takes the form of an

identification of the type X is Y, similar to the conventional metaphor in

poetry, but it has no direct expression in the language; it is realized through

instantiations, utterances which are

often taken to be non-metaphorical, since they do not take the X is Y form, but

are produced by concepts which are metaphorically built.

The concepts and thoughts -our conceptual system-

according to which we function in our lives (of which we are, needless to say,

unaware of), must be viewed in their relation to our actions and attitudes, as

reflected in our daily activities.

We have found... that

metaphor is pervasive in everyday life, not just in language but in thought and

action. Our ordinary conceptual system, in terms of which we both think and

act, is fundamentally metaphorical in nature. ... Our conceptual system thus

plays a central role in defining our everyday realities. If we are right in

suggesting that our conceptual system is largely metaphorical, then the way we

think, what we experience, and what we do every day is very much a matter of

metaphor.

This unified way of conceptualizing a domain of experience metaphorically is realized

in many linguistic expressions. For

example, the way we conceptualize an argument is almost completely structured

by the CM ARGUMENT IS WAR; in other words, our experiences of arguments depend

basically (and perhaps exclusively) on the CM just mentioned. Briefly, this

means that the way in which we conceive an act of war is partially used to

understand (and therefore to act towards) arguments; we think of and experience

arguments as if they were, in most aspects, armed conflicts. Language is a

reflection of how our minds work in understanding things, and therefore it is

not surprising that the evidence validating this proposal consists of hundreds

of linguistic expressions which demonstrate the way we conceptualize

metaphorically pieces of language that we try to understand or assume to be

literal (or, in ontological terms, true), though no speaker of English may say

that an argument is a war is a common

saying, because this CM is not actually part of the language. There is plenty

of examples of colloquial, everyday

linguistic expressions, used commonly throughout the world, which show a

systematic way of talking about an argument as if it were a war situation:

Your claims are indefensible.

He attacked every weak point in my argument.

His criticisms were right on target.

I demolished his argument.

I've never won an argument with him.

You disagree? Okay, shoot!

If you use that strategy,

he'll wipe you out.

He shot down all of my arguments.

The authors describe the metaphorical process as a mapping (in the mathematical sense) from

a source domain (in this case, war)

to a target domain (in this case,

argument). This mapping is tightly structured, that is, there is a systematical

ontological correspondence between the entities in the domain of argument (the

participants, their claims, their ways of discussing) and the domain of war

(the parties, their weapons, their strategies).

The generalizations

governing... metaphorical expressions are not in language, but in thought: they

are general mappings across conceptual domains. ...the locus of metaphor is not in language at all, but in

the way we conceptualize one mental domain in terms of another. The general

theory of metaphor is given by characterizing such cross-domain mappings. And

in the process, everyday abstract concepts like time, states, change,

causation, and purpose also turn to be metaphorical. ...metaphor (that is,

cross-domain mapping) is absolutely central to ordinary natural language

semantics, and... the study of literary metaphor is an extension of the study

of everyday metaphor... characterized by a huge system of thousands of

cross-domains mappings.

Lakoff and Johnson adopted a mnemonic strategy for

naming these mappings, e.g., TARGET-DOMAIN IS SOURCE DOMAIN. In this case, the

name of the mapping is ARGUMENT IS WAR. When we speak of the ARGUMENT IS WAR

metaphor, we are using a mnemonics for the set of ontological correspondences

that characterize a mapping as THE ARGUMENT-IS-WAR mapping.

TARGET-DOMAIN SOURCE-DOMAIN

ARGUMENT IS WAR

Two aspects must be borne in mind concerning

metaphorical conceptualizations: they are partial and they are systematic. We

have said that metaphorical concepts are characterized by the structuring of

one concept in terms of another. This does not mean that we conceive of the

elements involved in a metaphorical relation as being the same, but rather as

being characterized by the same categories. What is essential is that only some of the aspects structuring

a concept are used to structure another. In the CM TIME IS MONEY, only the

aspects of the concept of MONEY which define it as a unit of measure and as a

quantifiable limited resource are taken into account (that is, highlighted);

its other characteristics, such as "used to buy things", are hidden

from the focus of our attention. Thus, metaphorical conceptual structuring is

necessarily partial.

Metaphorical concepts are systematic: they conform a

coherent system of metaphorical expressions, not random or isolated cases. We

can perceive a certain pattern in our way of talking about arguments, time, and

many other subject-matters; that is, we refer to them in some ways and not in

others. The interesting fact is that in the metaphorical relation we can always

distinguish between an element belonging to a well-defined domain of our

experience which is used to refer to another concept from a less clearly

defined conceptual domain. For instance, in the CM TIME IS MONEY, the

vocabulary taken from the conceptualizations we have of money reveals that it

is not clear to us the type of "thing" time is, and that in order to

think and talk about it, we need to borrow the concepts and the corresponding

vocabulary from another "thing", in this case, money. This process

does not occur in isolated or random instances, but rather in systematic and

coherent fashions of discourse.

So far we have been looking at CMs of a single kind,

namely, Structural Metaphors. There are at least two other types of

metaphorical conceptualizations, the ones called Orientational and Ontological

Metaphors. The Orientational Metaphor implies the global organization of a

conceptual system. Its name derives from the fact that most of them are related

to concepts defining spatial categories, such as HAPPY IS UP or MORE IS UP.

Ontological Metaphors are those whose bases are found in our experience with

physical objects (especially our own bodies) and with objects and substances

existing in our environments. Thus, in these cases, we will find projections of

entity structure to things and events, or the categorization of non-substance

elements as being substances. In effect, Lakoff and Johnson state that events

and actions are conceptualized as objects, activities as substances, and states

as containers. The most obvious case of Ontological Metaphor is that known as

Personification, in which the object defined is specified as if it were a human

entity. By viewing objects and experiences as human beings, we can give the

former the numerous characteristics attached to the latter. The function or

purpose we aim at when we use a concept is the relevant issue at this point: by

using such a conceptual and linguistic device we can express a greater deal of

information about the topic or about our inner experiences in relation to it.

The CM INFLATION IS AN ENEMY, for instance, allows us to say we must attack inflation, we are defending

ourselves from inflation, as if inflation were a human enemy involved in a

war situation, such as a battle. We must distinguish this case of

Personification from those of Metonymy (Met) or reference of one concept to

another related to it, as when we say, for example, Mrs. Grundy frowns on blue jeans, in which blue jeans stands for people

wearing blue jeans. We must, anyway, recognize that, the same as metaphors,

metonymies are used to have a better understanding of objects and experiences

that lack a clearly delimited or easily understandable conceptualization.

Metonymies are also partially structured and present systematicities in their

functioning as linguistic expressions, and they are very active in the cultural

sense.

The

Conceptual Metaphor approach also attempts to examine the nature of "folk

theories," models of some aspects of reality

that are most often taken as constituting "common sense". Folk

theories, according to these authors, involve conceptual metaphors from which a

chain of deduction emerges, e.g., from the CM SEXUALITY IS A PHYSICAL FORCE, a

speaker may assume, as these authors put it, that

physical appearance is a physical force> a woman is

responsible for her physical appearance...sexual emotions are part of human

nature...sexual emotions are a response to being acted upon by a sexual

force> a person who uses a force is responsible for the effect of that

force> a woman with a sexy appearance is responsible for arousing a man's

sexual emotions...sexual emotion naturally results in sexual actions> sexual

action against someone's will is unacceptable> to act morally, we must avoid

sexual action> avoiding sexual action requires inhibiting sexual

emotions> to act morally, one must inhibit sexual emotions...sexual emotions

are part of human nature> to inhibit sexual emotions is to be less than

human> a woman with a sexy appearance makes a man who is acting morally less

than human> to be less than human is to be injured (we have inserted the symbol

> to indicate the logical chain)

These deductions are not explicit. Speakers do not

follow a conscious chain of deduction since deductions have a logic and a

structure that remains unconscious behind the reality the speaker takes for

granted. According to Lakoff and Johnson, folk theories and CMs are easy to

understand "because they are deeply engrained in [American] culture...they

are largely held by people." They state that if metaphors and folk

theories are readily available to us for use in understanding, they are

"ours" in some sense, like the one in the example above, and that no

theory of communication or understanding can pretend to be adequate if it does

not account for the crucial role that CMs have on folk theories.

The theory of conceptual metaphor has given origin to a number of studies. A few of them are very briefly accounted for in what follows.

Kronfeld focuses his discussion about

metaphor on its very nature: are metaphors semantically special phenomena? Is

their meaning different from literal meaning? As she explains, most approaches

agree in that the meaning of a metaphor is not a function of the meaning of its

constituents, but instead it is a "new" and completely different

meaning; in order to discover this new meaning we need a "construal"

from the hearer/reader, i.e., a mechanism of some nature to actively construct

(produce) and deconstruct (understand) the meaning of a metaphor. Kronfeld

distinguishes two opposite approaches in relation to the idea of a construal.

The non-constructivist group claims that meaning is only literal meaning and

that metaphors have no meaning at all or are reducible to literal paraphrases,

rejecting the existence of construals. The constructivist approach postulates

the existence of a construal mechanism for understanding metaphors, but it extends

this mechanism to both figurative and literal language. Among supporters of the

last view we have several post-structuralist critics, such as Derrida, De Man,

and "experientialist" semanticists like Lakoff and Johnson, for whom

the puzzle of metaphor exists but it is not exclusive of metaphor.

Carbonell attempts to augment the power of a

semantic knowledge base used for language analysis by means of metaphorical

mappings. His central concern is the creation of a process model to encompass

metaphor comprehension.

Understanding the metaphors

used in language often proves to be a crucial process in establishing complete

and accurate interpretations of linguistic utterances.

Carbonell states that, although there is a set of general (conceptual) metaphors in

English, the majority of them are instantiated versions of a few general

metaphors, which he calls "common" metaphors, as opposed to those

which are "creative". According to this idea, the problem of

understanding a large class of metaphors may be reduced from a reconstruction

to a recognition task. The identification of an instance of one of the general metaphorical mappings is a much more

tractable process than reconstructing the conceptual framework from the bottom

up each time a new metaphor instance is encountered.

Each of the general

metaphors contains not only mappings of the form "X is used to mean Y in

context Z," but inference rules

to enrich the understanding process by taking advantage of the reasons why the

writer [or speaker] may have chosen the particular metaphor (rather than a

different metaphor or a literal rendition).

Carbonell's most important contribution is the Implicit-Intention Component: what the

speaker is contending when he/ she chooses to use a metaphorical expression

instead of a literal one. The hypothesis holds that this component is the

information about what the metaphor conveys that is absent from a literal

expression of the same concept; in other words, there is much more information

and expression intended in a CM than in a literal expression.

The issue of determining the Implicit-Intention Component is what Gibbs, in his own

terms, tries to arrive at through a series of experiments concerning the

semantic content and the presence of conceptual metaphors in idioms. He

postulates that idioms have complex figurative interpretations that are not

arbitrarily determined but are motivated by independently existing CMs that

provide the basis for a great part of everyday thought and, therefore,

language; idioms cannot be simply defined, as do dictionaries, as equivalent in

meaning to simple literal phrases.

...literal paraphrases of

these idioms [blow your stack, flip your

lid, hit the ceiling] such as "to get very angry" do not convey

the same inferences about the causes, intentionality, and manner in which

someone experiences and expresses his or her anger. ...[literal paraphrases]

are not by themselves motivated by single conceptual metaphors and therefore do

not possess the kind of complex interpretations as do idiomatic phrases.

Gibbs' inquiries show that idiom use and comprehension

vary depending on how discourse encodes information. This process is partially

motivated by entailments of CMs. This also holds for Carbonell's instantiations of a CM, even though he

only analyses them in single sentences. Both positions can be bridged at this

point.

Comments

Post a Comment